Littering: Why this sign won’t improve littering

by Livvy Drake

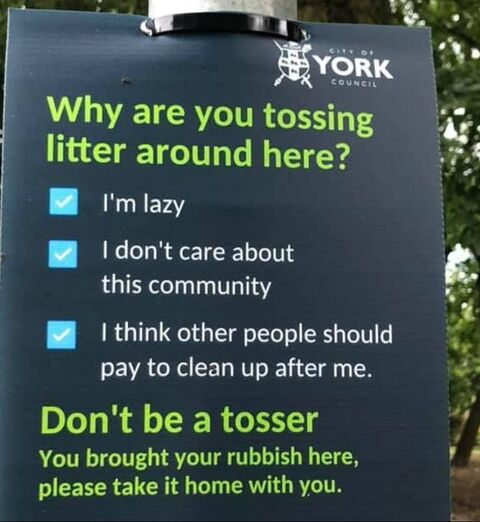

Why ‘ Don’t be a Tosser’ signs will not address the reasons people litter

This summer the spotlight was on littering as people emerged from lockdown and appeared to show ‘disregard’ for the only places available to socialise in – parks, beaches and the great outdoors.

There was outrage, disgust and vilification across social media about the littering behaviours. This was replaced with an equal measure of positivity about signs like the above appearing in public places, later in the summer of 2020.

However for people like myself who have worked in festivals and events addressing audience littering behaviours, putting up signs like this certainly were not the solution.

From a behavioural psychology perspective here are three reasons why this sign simply acknolwedges the reason people litters rather than trying to change them.

1. Cost- benefit analysis

Our brains are wired for short-cuts, the easy option and to reduce effort and energy exertion. Behavioural economics talks of perceived effort and perceived benefits. This means that when our brain decides to carry out a task, it considers how difficult it thinks it will be (2/3rds of our understanding is just perception not reality) and if there are any benefits (what’s in it for me).

What does this mean for the sign? In answer to number 1-

Yes, if there is not a bin immediately available, a person may decide that it is too much effort and there is no benefit to carry unwanted packaging. And certainly carrying it all the way home.

How can this be addressed:

- Putting bins in places where there is high incidence of littering or food consumption and putting recycling and general waste bins together.

- Packaging having a value – the introduction of deposit return schemes (Scotland 2022, UK 2023) will go some way to address this for bottles and cans.

- Working on local reusable coffee cup and bar cup schemes to reduce the single-use materials being generated in the first instance. Shrewsbury Cup is an example of this.

2. Herd mentality

The biggest litterers are generally young people between ages of 18-34. This is often done as a sign of rebellion from wider societal expectations to fit in with their peer group and appear ‘cool’.

Furthermore, humans look for cues in areas to understand what is the social norm in a particular area, so the appearance of litter suggests that it is socially acceptable. Research has shown that with 1-2 pieces of litter, (78% and 90% of people, respectively, used bins) with more than three pieces of litter, litterers increased by 41%.

In a Metro article Dr Konstantinos Arfanis – a lecturer in psychology at Arden University suggested that the pandemic had changed so many social norms that ‘Social conventions become irrelevant, we have to learn again how to behave publicly.’ In the same article Professor Margareta also suggests that littering could also be a sign of rebellion following the enforced lockdown. ‘This could be a subconscious way to break out of the “forced- upon” compliance they had to adhere to‘.

It is certainly the case at festivals that people see them as a place to let go of all the daily restrictions and new ‘social norms’ are constructed.

What does this mean for the sign? In answer to number 2 –

Yes, they may care more about fitting in with their own social circle than with the local community. They may also feel that the local community does not care either depicted by the existence of rubbish. Research by Beaufort (2010) found litter can be more prominent in areas of social deprivation, where it is seen a minor issue in the scheme of things especially if an area is run-down.

Overflowing bins are also a sign that the local authority do not care either.

How can this be addressed:

Shambala festival provides a good example, as they worked hard to avoid the littering ‘tipping point’, by never letting bins overflow and doing litter picking at night when people were becoming less ‘responsible’. They also worked hard on building strong environmental and community values into the festivals values and social identity of ‘being a Shambalan’. In a survey I conducted whilst working there, people said they would leave their tent at other festivals but not at Shambala because it wasn’t socially acceptable.

Of course, councils and parks are struggling with the volume of rubbish and managing bins during the pandemic, but increasing bin empties and further infrastructure would help the situation.

And if signs did go up they should be focusing on how many people do not litter in the local community e.g. xx of people from xx location put their rubbish in the bins in this area. Or showing relatable figures carrying out the desired behaviour.

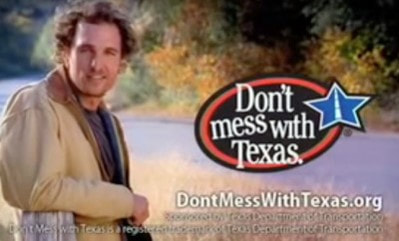

The most effective US littering campaign was the ‘Don’t Mess with Texas’ campaign which linked Texan identity with not littering using famous Texans and bumper stickers.

3. Tragedy of the commons

There are many ways that littering in public places is a tragedy of the commons- a situation where people acting out of self-interest impact on common goods and resources, whilst not seeing it as their responsibility.

- People think their one piece of litter won’t make a difference

- There is a lack of sense of shared responsibility and care for public places because taxes are paid to ‘clean and maintain them’ – it’;s the councils responsibility

- People buy the goods inside packaging, not the packaging so they don’t value it. Although the manufacturers have actually sold them the packaging because they also don’t want to take responsibility for it or get it back. It has also now been created to be so low value that it has no value for recyclers either.

What does this mean for the sign? In answer to number 3 and the final statement –

Yes people do think the council is responsible or someone else.

How can this be addressed:

- Campaigns to get big brands to take responsibility for their packaging has lead to Terracycle schemes to manage hard-to-recycle materials which support local community groups to collect these materials with rewards for the groups. Developing ways to collect these at scale in public places or to get back to local groups would give value to the materials.

- Building connection with local communities and spaces with regular community clean-up days

- Kolodko and Read suggest that rather than targeting the harder to reach groups

Targeting interventions at groups with lower barriers to change not only increases the chance of the intervention being a success, but also maximises the chance of reaching a tipping point (Grodzins, 1958), at which a social change spreads on its own

Of course for local authorities have significant financial restrictions upon them, so putting up a sign is a cheap solution. But I would argue if they were to invest in these they consider the audience they are addressing and their motivations rather than expressing the values of the people writing the sign. To me these signs are little more than ‘virtue signalling’ to the wider community who don’t litter.

If you create signage and posters to communicate pro-environmental behaviour and you would like more tips check out this blog on the 5 reasons facts and stats do not work.

Want all the insights into Waste and recycling, watch the Waste 101 recording

Engage people outside the echo-chamber and inspire action for your cause!

If you would like to make your campaigns more effective by applying the principles of behavioural psychology, watch our on demand workshop specifically designed to help environmental campaigners and communicators achieve greater behaviour change for the environment.

And for more tips you can always join our newsletter.

You might also like: